Introduction

Assuring chain of custody for electronic evidence is more complicated than for other types of evidence, such as a gun, for instance. One of the reasons for that, is that electronic data can be altered without leaving obvious traces. That is why one of the most natural questions which the counterparty may, and will ask in court is: 'How can you prove that this evidence (chat/document/photo) has not been altered?' And that is why, apart from well-known actions for preserving chain of custody (like maintaining chain of custody forms), there are additional methods for digital forensics.

This article explains these methods utilizing Belkasoft X, a flagship digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) tool by Belkasoft.

Data collection stage

This is the first stage of every DFIR investigation and is where a chain of custody first appears.

Let us skip the collection of the physical evidence, as we would for non-DFIR items. Digital forensics specifics start at the point of data acquisition. Here, we will focus on what can be done wrong during this stage and what will invalidate the chain of custody.

Working with the original data source instead of a secondary "working" copy of the acquired image will almost inevitably introduce changes to the data. Even if a file’s content is not changed by an investigator, any actions such as file access will change its properties. Though it sounds unlikely for an educated digital forensic investigator, we continue hearing about the use of the original drive, and even the original live system for an investigation. An example of this type of action, could be opening a browser on a running computer of interest and looking through the latest sites visit history.

A slightly better, but still risky approach would be to work with the original data source that is protected with a software based write blocker. Software write blockers are notoriously known to not block write attempts due to errors, but this is not the only issue that they may have. The following article outlines an excellent overview of what may go wrong while using a software based write blocker.

If you are using hardware write blocking devices, remember that SSD drives cannot be fully protected with such a device. The investigator must be aware of the following potential SSD changes that can irregularly and will inevitably occur, such as TRIM or garbage collection.

The industry standard approach to data acquisition is to create a clone disk or an image of the original device. During the acquisition, the original device must be protected with a hardware write blocker (even though we know that SSD’s are not fully protected against data change, this is ultimately the best thing one can do, unless the SSD contents are not encrypted allowing for possible invasive methods of acquisition).

Can anything go wrong and affect the chain of custody even with this approach? Yes! One example would be if one were to clone a hard drive but forgets to sterilize the receiving drive first. If you have not correctly wiped or formatted the drive to work as a clone of the evidence drive, you can get unpleasant surprises originating from older cases, such as artifacts recovered by carving.

To preserve the chain of custody, an examiner must make sure that the data acquired matches the contents of the device being acquired. Possibly the most well-known method for this is hash calculation. It is a good practice to calculate a hash sum for the entire data source and all files inside, before doing any further analysis. Common mistakes during this portion of the investigation could be:

- Not calculating hash values at all. No further comments required.

- Using MD5 only. This algorithm is prone to collisions and, if used, should be complemented by another one, such as SHA1 or SHA256 (Note this link on SHA1 future).

Unfortunately, most of problem sets discussed above are not feasible for modern devices. You cannot acquire all the contents of a modern smartphone: there currently is simply no method for this provided by a vendor. Hash calculation is great but it will inevitably give different results for data acquired from a mobile phone, meaning that the two consecutive acquisitions will have different hash values, ensuring nothing.

Generating hash values will also not work for memory dumps. Due to the importance of information (particularly, related to encryption) stored in volatile memory, RAM capturing is a vital stage of data acquisition. However, calculating hash values for a RAM dump makes little sense to prove it matches the original data.

Finally, if for any reason an investigator has to make an image of a running computer or a laptop, hash values will also be naturally different for two consecutive acquisitions.

Having said this, it is still required to calculate hash values to ensure that obtained images and dumps are not amended after the acquisition stage.

To help you assure the chain of custody during the data collection stage, Belkasoft X includes features to forensically acquire hard and removable drives, mobile devices, RAM, and cloud data. The product supports MD5, SHA1, and SHA256 hash calculation for both the images and the files inside.

Examination stage

During the examination stage, you must document actions you take within your DFIR tool, to maintain the chain of custody. An examiner must answer the following questions during examination, as the forensic analysis must be repeatable. What was your tool configuration? What types of searches did you schedule? What were the results?

Under this stage, Belkasoft X can help answer these questions, utilizing the following methods:

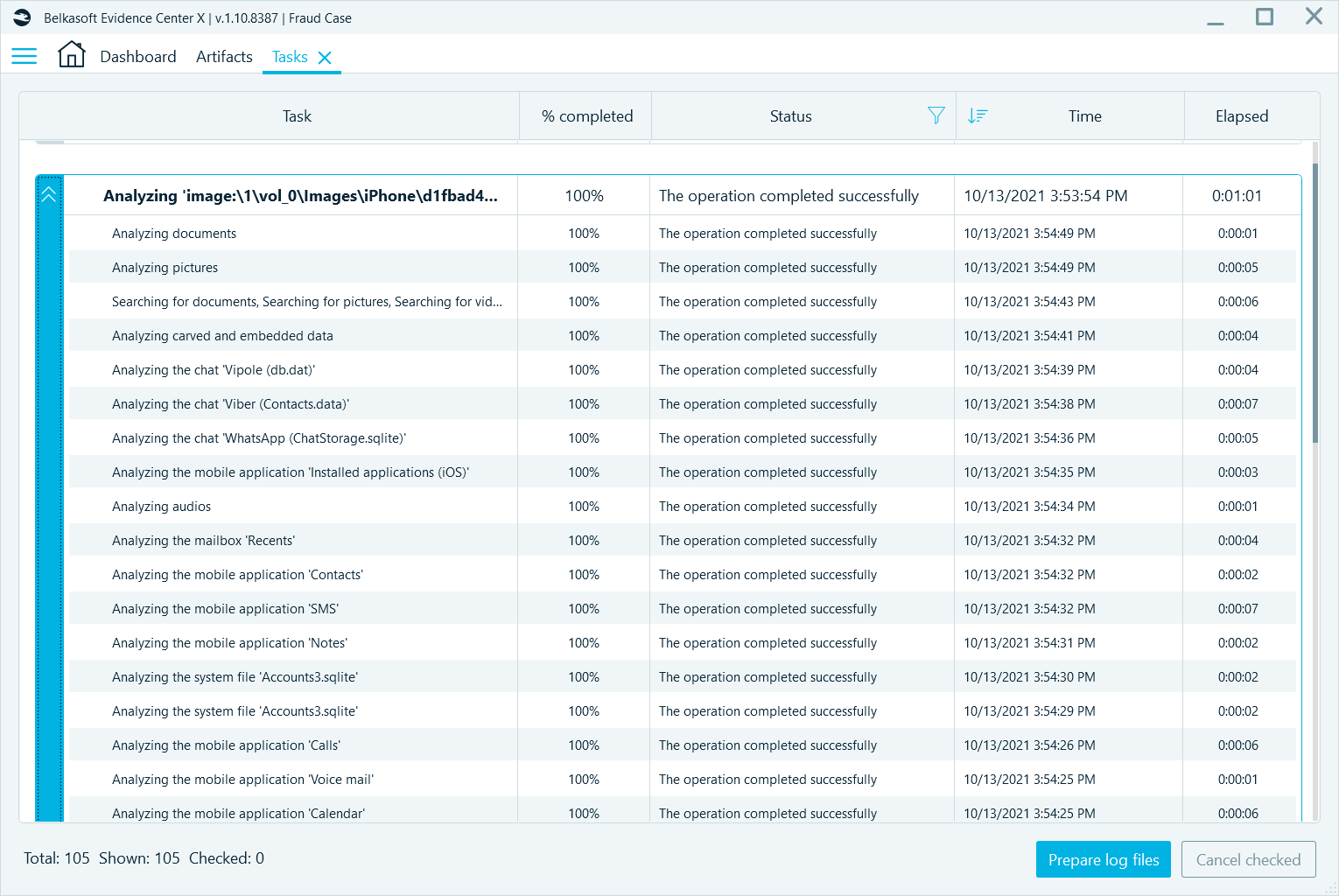

- Under the Tasks window the product shows an examiner all tasks that have been run for a particular case. These tasks are stored in a centralized database and will be shown even if you re-run the product or re-open the case.

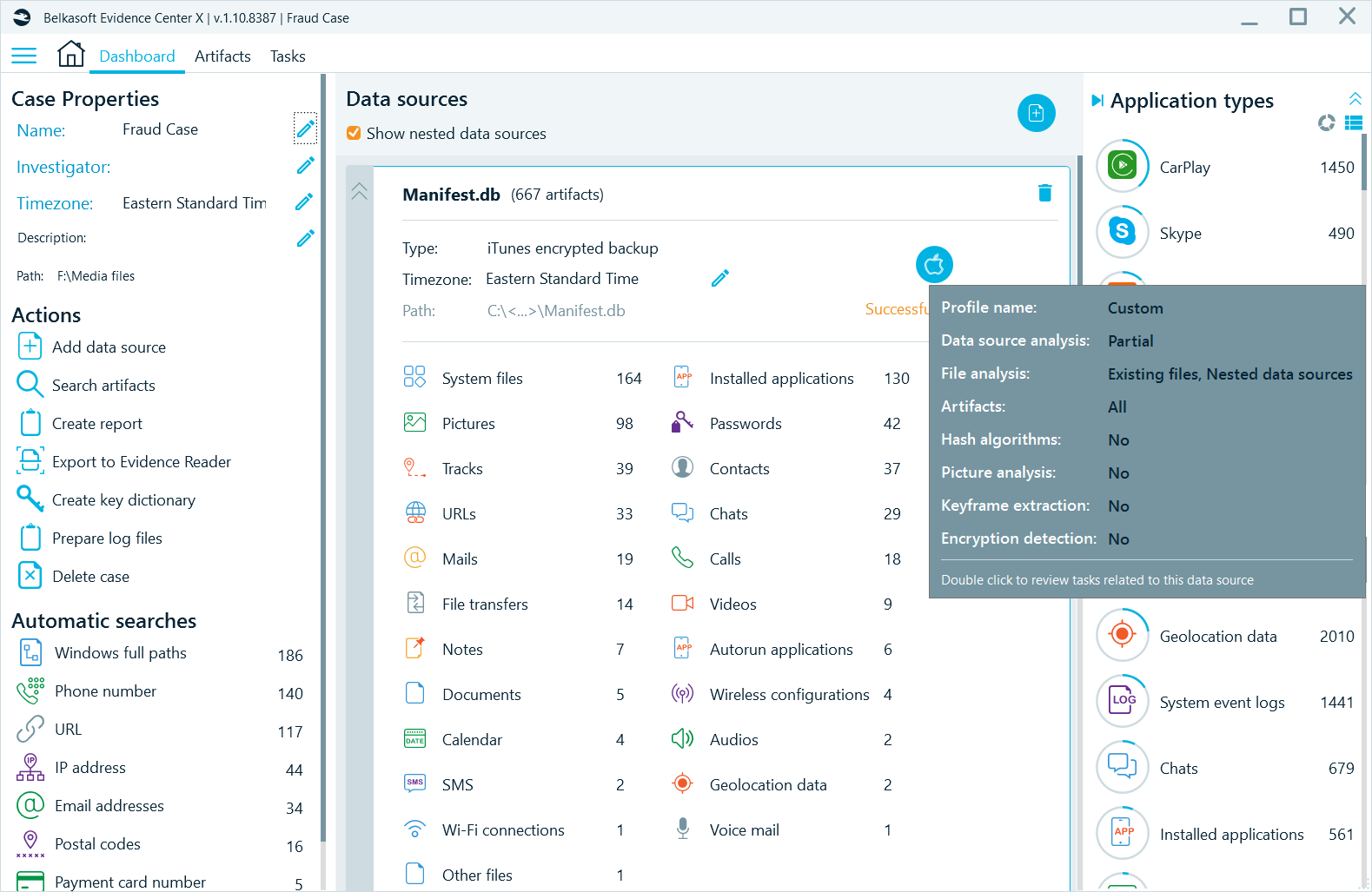

- On the Dashboard, you can review options of analysis that have been run for every data source, by hovering over the data source type icon:

- The product conveniently gives you information such as the case creation date and time, the investigator’s name, case notes, and so on.

- For every piece of information, which Belkasoft X recovers out-of-the-box (such as a chat, a browser link, a document, a picture, etc.), the product maintains its Origin path thus helping you to explain where this particular artifact was extracted from.

Analysis stage

There are a number of analytical functions within the Belkasoft X that an examiner can use for the analysis stage, such as photo classification, connection graph visualization, timeline visualization, and more.

There is no specific means included within Belkasoft X for assuring chain of custody for this stage. However, just like within the examination stage, one can see actions that have been run within the product, such as searching for faces within pictures, or hash set match detection, or OCR, in the Tasks window.

The examiner can also include visual information such as a Connection Graph for selected entities and even applied filters, into a forensic report. To do this, one can simply use the built-in reporting function within the Connection Graph window.

Reporting stage

It is important to mention that your DFIR tool report is far from enough to assure a chain of custody. A digital forensic software product includes just a small fraction of what is ultimately needed to ensure a proper chain of custody. An examiner must complement the reporting functions within a product with explanations of what additional tools were used, what the data sources were, how the data was acquired, how the integrity of the data was ensured, and how the data was examined and analyzed. To withstand in a court, your report must clearly describe how the chain of custody was maintained during the entire case.

Since this kind of information is typically out of sight of a DFIR tool, it will not fully provide all the necessary components of chain of custody during this stage. Your organizational templates and best practices will.

All stages

One important issue that needs to be addressed when dealing with the chain of custody, and which relates to all stages, is that an examiner does not only have to maintain the list of everyone who touched the evidence, but they must also ensure that no one else has access to the data. Since the electronic evidence exists virtually, there are more ways to occasionally allow such access, than to a physical piece of evidence, such as a gun. For example, leaving a cloned hard drive on a desk in a room, where other investigators work at the same time, breaks a chain of custody. Similarly, leaving one's computer unlocked can potentially invalidate all evidence files stored on that computer.

For a mobile device it is easy to break a chain of custody by leaving just one of the access protocols switched on, including cellular connection, WiFi, or Bluetooth protocols, for a device not protected by a Faraday bag.

Conclusion

Preserving the chain of custody is vital for evidence presented in a court. Not preserving it, or the inability to prove it has been preserved, or even a minor issue with a single step in the chain, may invalidate the examiner’s entire evidence collection and possibly deem the examiner’s entire investigation inadmissible in court.

When it comes to digital evidence, there are even more mistakes that can take place within this process than with a physical evidence item. The examiner must be aware of these precautions and use best practices described within this, and many other similar articles on the topic. It is advised that the examiner understands their DFIR tool’s functionality facilitating the chain of custody maintenance, including forensically sound acquisition methods, their applicability, hash calculation, and more.

Belkasoft X provides you with a number of useful options to prevent issues with chain of custody.